|

|

Porter Wagoner 1927-2007

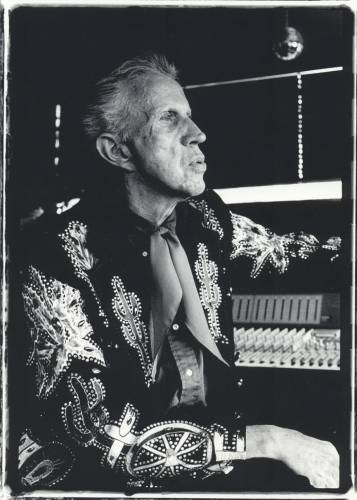

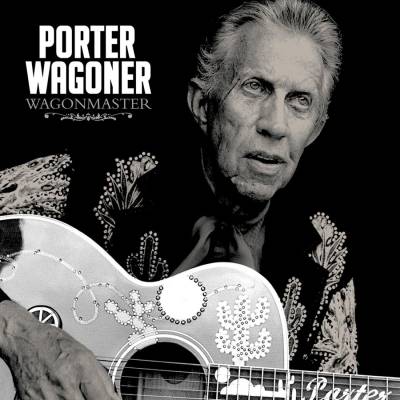

By Bob Doerschuk © 2007 CMA Close Up News Service / Country Music Association, Inc. Used with permission. When Porter Wagoner, known as "The Thin Man from West Plains" because of his lanky frame, succumbed to lung cancer, at 8:25 PM/CST on Oct. 28 in Nashville, a piece of Country Music history slipped into its rhinestone-studded jacket, stowed its guitar and headed toward the stage door. Wagoner, who had survived an abdominal aneurysm in 2006, made his exit quickly, being hospitalized on Oct. 15 and released to hospice care on Oct. 26. But before then, he had flourished for half a century as a member of the Grand Ole Opry, pioneered the fusion of Country Music and television as host for 21 years of "The Porter Wagoner Show," won three CMA Awards and four Grammy Awards, helped Dolly Parton and Mel Tillis launch their careers, and then joined them in 2002 as a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame. In addition to these accomplishments was the impact Wagoner made on countless fans who embraced him as one of their favorite entertainers. His homespun humor and accessible vocal style captivated radio listeners for generations. The gaudy outfits, upswept hair and room-lighting smile were indispensible elements in his live shows - but for those who could only listen from hundreds or thousands of miles away, the sound and feeling of the man, as broadcast from Nashville, were enough to make him seem like a friend. "This is a terrible loss for the music industry on many different levels," said CMA CEO Tammy Genovese. "Musically, the 'Wagonmaster' contributed a great deal to the format with his voice, his humor and his undeniable charm. He was a consummate showman, wrapped like a bright and precious gift to the nation in his trademark rhinestone-studded suits. He is an unforgettable figure in Country Music history. He will be missed. Our prayers go out to his children Debra, Denise and Richard and their families." Porter Wayne Wagoner was born on Aug. 12, 1927, in the Ozark Mountain region of southwestern Missouri. Raised in West Plains, educated in a one-room schoolhouse, he worked as a young man by day in a butcher shop and as a Country performer at night. His style grew from its bluegrass roots into a synthesis of Roy Acuff, Hank Williams and other contemporaries, blended with Wagoner's own evolving sound. In 1951, he became a regular on the KWTO program, out of Springfield, Mo., that would become "The Ozark Jubilee." A year later he made his recording debut for RCA Victor, and the following year Carl Smith turned Wagoner's "Trademark" into a hit. "A Satisfied Mind" hit No. 1 in 1955 and conveyed Wagoner to Nashville and membership in the Grand Ole Opry two years later. In 1960, he launched "The Porter Wagoner Show." Its mix of traditional Country Music, comedy sketches, and guest shots by established and upcoming stars helped it earn syndication to more than 100 television stations and expanded its audience to more than 3 million by the early '70s. It also introduced the world to Parton, Wagoner's protégée and duo partner. Through their seven-year association, they won three CMA Vocal Duo of the Year Awards, earned a Grammy and cut 14 songs that wound up in the Top 10, including "Just Someone I Used to Know," "Making Plans" and the chart-topping "Please Don't Stop Loving Me." In his solo work, Wagoner reflected extraordinary range. His songs, whether self-penned or selected to reflect the complexity of his artistry, combined elements that would seem incompatible in the hands of a lesser artist. Yet Wagoner displayed consistent insight as an interpreter, whether delivering gospel songs, playfully humorous material, stoic recitations or descents toward the depths of a tortured soul. From "Company's Comin'" (1954) and "Eat, Drink and Be Merry (Tomorrow You'll Cry)" (1955) through the stark, fiddle-haunted introduction to "Albert Erving" from his last album, Wagonmaster (2007) produced by Marty Stuart and released on ANTI-Records, from his gigs with the Blue Ridge Boys in his early 20s to his appearance in July as the opening act for The White Stripes at a sold-out show at New York's Madison Square Garden, his legacy is unique and secure. "I may not be the world's greatest singer," Wagoner said in his 2007 interview with CMA Close Up. "But I know how to sing Country Music. I know what separates Country from other kinds of music. I've learned that it's important, if you're a singer or an entertainer, to know what you're doing. You need to study this business as if you were going to be a doctor, a lawyer or a man that makes big decisions. You never do find out all there is to know in your lifetime. But you learn from that process every day - and you don't forget what you learn." Amen, Porter. Porter Wagoner: Wagonmaster

By Bob Doerschuk © 2007 CMA Close Up News Service / Country Music Association, Inc. Used with permission. He'd grown up watching "The Porter Wagoner Show" in Mississippi; he even appeared on it, as a prodigy picker at age 13. The resurrection of these memories, one fateful day not long ago, was the first step toward the work that would lead this year to Wagoner's latest album, Wagonmaster, on Anti Records. "That all came back on the day the war started in Iraq," Stuart said, relaxing at the Tennessee State Museum amidst his collection of Country Music memorabilia several weeks before it would be exhibited as "Sparkle & Twang: Marty Stuart's American Musical Odyssey." "There was CNN coverage all day long. I watched as much as I could stand and then went to the back of the bus to take a nap, just to get away from it. Then, when I came back to the front, 'The Porter Wagoner Show' was on the RFD Channel. I watched the entire show, and when it was done I felt like I did when I was a kid: as bad as things can be, it's going to be OK." Wagonmaster grew around the sound that Wagoner cultivated on his show. Between the blazing hoedown fiddle that kicks off the "Wagonmaster" theme to the last moments, a stark solo rendition of "I Heard That Lonesome Whistle Blow" during the final moments of "Porter and Marty," the album's last track, these performances transplant Wagoner's roots into a conceptually adventurous setting. On 17 songs, nine of them written or co-authored by Wagoner, every facet of his persona comes into view, from the playful side he displays at the Opry ("Be a Little Quieter") to the dark corners of the soul he'd explored in his classic 1972 recording "Rubber Room" ("Committed to Parkview," written by Johnny Cash and given to Stuart in 1983 to pass along to Wagoner. That this request slipped Stuart's mind until now may prove all for the best, given the stark and scary eloquence that Wagoner brings to the tune today). Wagoner's voice is worn yet irresistibly expressive, whether meditating on the fleetness of life's passage ("A Place to Hang My Hat"), recounting the stories of strangers on a bus ride toward their diverse destinies on a Wagoner-Parton co-write ("My Many Hurried Southern Trips"), remembering a hermit who harbored a heartbreaking secret ("Albert Erving"), or even just talking on tape with Stuart about Hank Williams. On "Brother Harold Dee," though, Wagoner achieves a transcendent eloquence through the now neglected device of recitation. "Red Foley taught me how to do that. I got to know him real well in Springfield, Mo., where he was doing 'The Ozark Mountain Jubilee,'" he recalled, noting the radio program on which he was featured until joining the Opry in 1957. "He knew how to talk to an audience. He told me one time, 'You can't talk over an audience, because there are hundreds of them sitting there. So if you lose their attention, talk softer. They'll listen harder.' And it works." The impact of Wagonmaster owes much to Wagoner's gift for bringing characters to life, as a writer, a vocalist or both. "I try to put myself into every song I project, in a way that makes it sound as though I've been there. Now, most of them, I have not been there. I never tried any of the drugs because of my fear for it. But I've always had a softness for people who get hooked on whiskey or some type of drugs. In order to sing this way, you've got to believe that you somehow have it in yourself. 'The Late Love of Mine' was unique in this way because I wanted to project that the guy was telling this story as though he was a drinker." And here Wagoner began to sing the slow, sad waltz of this track from Wagonmaster: "How can I expect a good woman to love a slave of the wine? I knew that someday I'd lose her, the late love of mine." With that, we're taken somewhere far from here, to wherever that place is that feeds the genius of Country Music when it's allowed to flow freely and poetically. It was this place that Stuart visited, not long after that that incident on his tour bus, when he dropped by Wagoner's home one night and left knowing why he would produce, play on and help his friend bring Wagonmaster into the world. "Porter was ready, man," Stuart remembered. "He had song after song after song. The more I sat there, listening, the more I thought, 'This is why I fell in love with Country Music, right here.'" |